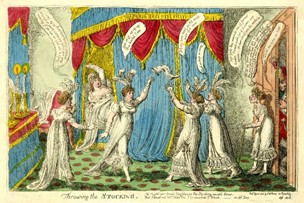

Throwing the stocking

Here, as vaguely promised, is the start of a short story inspired by yesterday’s completely random search for inspiration (see yesterday’s post if you missed it). This is draft one, off the top of the head, with minimal thought or editing. And where the story goes from here is, at the moment, anyone’s guess. I have an idea and I may carry on and complete the story once I have figured out the point, shape and progression of it. But here, interspersed with random images, is the opening ‘set-up’ of a story called ‘Throwing the Stocking.’ It is quite long for a post so bear with it, maybe settle in with a cuppa and, hopefully, enjoy.

The Duke and Duchess of Quendon were known for their tireless efforts to uphold failing British traditions. The Duke was still the holder of the title of ‘Essex Conker Champion’ and had been since 1793. Now, over thirty years later, the much coveted trophy was still his to show off, remaining undefeated for many more years than any local conker opponent would care to remember. The trophy stood on his ornate drawing room mantelpiece, displayed with all the pride of a first born son, alongside other trophies he and his wife had been awarded for their efforts in mud walking, gravy wrestling and hobby horse droving.

The Essex Conker Champion trophy took the form of a tall, blue-glass vase, crafted with exquisite chestnut tree designs and showed a pair of ornately dressed aristocratic men beneath it, politely playing with their conkers. One was holding up his nut on a lace while the second was having a really good go at it with his own. Only the Duke polished or touched this trophy; even the footmen had to wear gloves just to look at it. It was the talk of every single after dinner conversation that had been held in the room for the last thirty years at least and was only brought out on County Conker Day when the Duke arrived at the autumn fayre to defend his title.

The day he had first won the trophy and title was as clear in the Duke’s mind today as it had been all those years ago. He had been a boy of eighteen, entering the seniors’ competition for the first time. The event was held on a balmy autumn evening, the same day that ‘The Reign Of Terror’ began in France (quite by coincidence). The ‘Young Earl’, as he had been then, had prepared his large conker meticulously. It was a ten-er even then, heavily vinegar-soaked and shiny, in fact, not unlike the Duke himself, had the vinegar been brandy. With the aid of his valet, the Duke and prepared himself just as meticulously, arriving at the event in his finest, most florid garments in order to impress the daughter of his uncle’s second cousin, the Lady Louisa Labouquet, who he knew loved to watch conkers as much as he loved to play them.

The competition had been fierce, there had been a dispute over shoelace-length and pendulosity and the Earl very nearly lost on a technicality. However, with Lady Louisa’s father, Lord Louis Labouquet, as the judge, the outcome was known even before the preliminary rounds were underway. The Earl’s opponent was disqualified for un-gentlemanly behaviour; having raised the unpalatable suggestion of cheating, the man was horsewhipped for simply saying the word. The judge, it seemed, was more impressed by the young Earl’s inheritance and title than he was with his technique. He was completely overwhelmed by the young man’s generous, some might say extravagant, attentions he had paid to his, let’s face it, rather bovine daughter, Lady Louisa.

On that great day over thirty years ago, the Earl had won not only the ample hand of his beloved in marriage but also the championship; a championship he had won every year since, using the same conker, now at least a forty-er. (There was a rumour that his miraculous conker was actually made of glass or stone. The Athenaeum, in 1808, had first mentioned this possibility; in 1814 the topic was cautiously aired in Lady’s Monthly Museum – Polite repository of amusement and instruction, but the claim was refuted in The Monthly Intelligencer one year later. The actual all-winning conker’s safekeeping place was a closely guarded secret. In fact, only the Duke knew where he kept it and only then on his more lucid days.)

The blue-glass trophy-vase on the Coadestone mantelpiece was, therefore and to say the least, the Duke’s pride and joy.

The Duchess, on the other flabby hand, had two pride and joys. The first was her daughter.

The Lady Sophia had gestated unnoticed in her mother’s womb for the full term. Her presence had been safely protected behind years of indulgence manifest as fatty folds and camouflaged under an adjustable corset, shift and three layers of expansive, unspecified garment that Lady Louisa always wore, even in her retiring chamber. The child arrived quite unexpectedly somewhere between the fish course and a stuffed widgeon at a dinner held to celebrate a visit by the Marquis of Bottom-Whallop in 1805. The Duchess put the sudden pains down to Cook’s stab at a syllabub starter and the embarrassing, not to mention carpet-ruining, gush of ‘waters’ down to the liver powder that ancient Doctor Scrivener had prescribed to her back in 1799. However, there was no easy explanation for what slipped out next. It took two footmen, the butler and two hastily summoned stable lads to manoeuvre the Duchess into the green drawing room. Once there, the gentlemen at the dining table were able to converse without the inconvenience of childbirth and Ivy, a long serving kitchen maid, was called to attend to the Duchess with instructions to bring clothes pegs and scissors. Ivy, who had been busy dressing the widgeon, had already given birth to twelve would-be kitchen maids and porters and knew her way around inter-course birthing. Sophia was finally served to the Duke and Duchess in the green drawing room at ten minutes past the port, a beautiful healthy baby girl.

Despite being born before the gentlemen had lit cigars, Sophia thrived and, as the years went quickly by, became the talk of polite society. Luckily for her she had not inherited her mother’s looks or cravings, remaining slim, divinely pretty and virginal to the very day. It was remarked, in pubic society, that she must have taken after her father. It was also agreed, in less polite private society, that she bore a great resemblance to the Duke’s chauffeur who was also rather slim and divinely pretty, but hardly virginal.

The Duchess’s second great pride and joy was contained in a small glass vial she always wore around her neck. Sometimes it would be found floundering in her ample bosom, sometimes it clung to the precipice of her cleavage on a silver chain, at other times it was hidden in the folds of majestic though unnecessary garments the Duchess was partial to wearing. She was often seen clutching it while taking a stroll in the manicured grounds, or playing cards with ladies in the yellow morning room, deriving some kind of inspiration for life from its clear, miraculous presence.

The vial was about four inches long, cylindrical in shape, it had silver ends and a silver screw-top with a tiny diamond added later as its centrepiece. It was said to contain the actual tears cried by the Mother of Jesus as she wept at the foot of the cross and it reminded the Duchess every day of their oldest and most fervently upheld traditions; those of the Church. Had she known, of course, that what it actually held was the sweat of the local Abbot, scraped from him by novice teens during his daily steam in his private quarters, she may not have been so fervent about it. Strangely, though, the charmed liquid had helped at least one dinner guest back to their feet after a particularly tricky run-in with a halibut and so the Duchess swore by it.

The Duke and Duchess were traditionalist of the highest order, so when it came to the marriage of the unexpected and beautiful Sophia, their only daughter, there was no question about it: all traditions must be adhered to and all had their place. As the wedding day approached and everything was made ready, the Duke rounded up a group of the most handsome local squires and first-borns and invited them to the very old and traditional event known as ‘Throwing the Stocking.’ In their defence, a lot of the first-borns had no idea about this ceremony, as none of them were old enough to be married yet and secondly because they had never been to a wedding where the bride’s stocking was removed, let alone thrown. In this day and age it was more common for the garter to be thrown and, in some very avant garde households, even a bouquet of flowers. The stocking-throwing was an older tradition even than the garter-throw and many friends of the groom had been keen to see how it was played out. They were also, some suspected, quite keen to grab a feel of a lady’s hose in order to offer them a little preparation for married life.

Thus, on this glorious day in June, the Duke stood at his mantelpiece beside his pride and joy blue-glass vase and addressed the cavalcade of well-dressed, though slightly bemused, younger men, all friends of Sophia’s intended, all from the county and all rather keen to get their hands on a lady’s stocking in some legal fashion.

To be continued? We shall see.