I woke up slightly late this morning, and the first thing I had to do? Waterworks, obviously. Not mine, the ones on the bathroom roof. Long story, but I had to reattach the mains feed pipe because, late last night, we heard a strange sound coming from the bathroom, and traced it to the water tank, which was, at nine at night, taking in water. However, the join had sprung a small leak, but I wasn’t fiddling around with spanners at that time of night, so we turned it off (the tank was miraculously full), and I have just seen to it. I now know enough about plumbing to confidently wield two adjustable spanners at the same time, and I understand the use of the mysterious white tape, which seems to fix everything. I hope. The mains is due to come back on soon, so I will see if I have fixed the drip. If not, Laki is coming on Saturday to give me a price for some odd jobs, and I’ll ask him to do it properly. Anyway…

The second job of the day is to tell you where you can find my books. This is in response to an email I just had in, which I will reply to in a moment. Basically, the books are over there on the left where it says ‘order online now’, but you can find all of them on Amazon (Kindle, paperback and KU) if you follow this link: James Collins Symi Books.

That’s the Amazon UK author page; you can substitute the .co.uk for .com and find the USA one, and they are also available from other countries’ Amazon stores.

The third job of the day is to remind you about the unique Symi calendar that you can only order from Lulu.com. This link, Symi Dream Calendar will take you there. As the blurb says, The Symi Dream Calendar 2026 This exclusive Symi calendar gives you 12 photos of Symi, an island in the Dodecanese, Greece. Includes views of Yialos, Pedi, Nimborio, Ag. Vasilis, Horio and Panormitis.

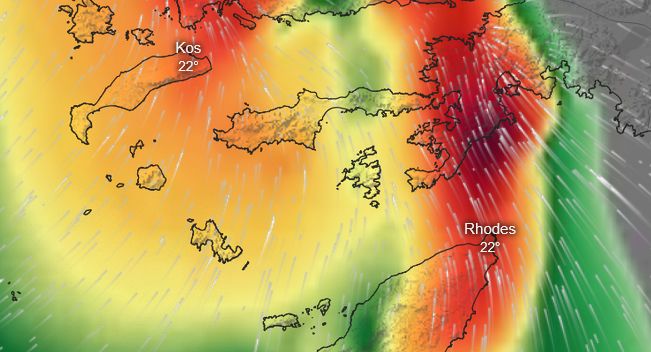

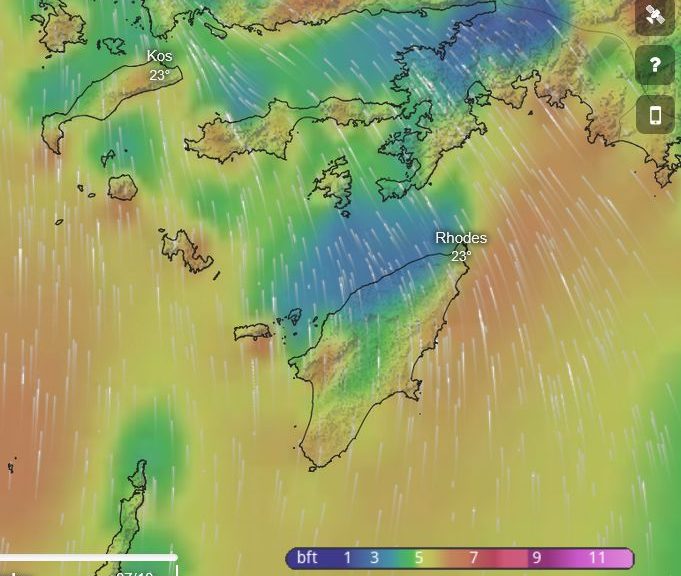

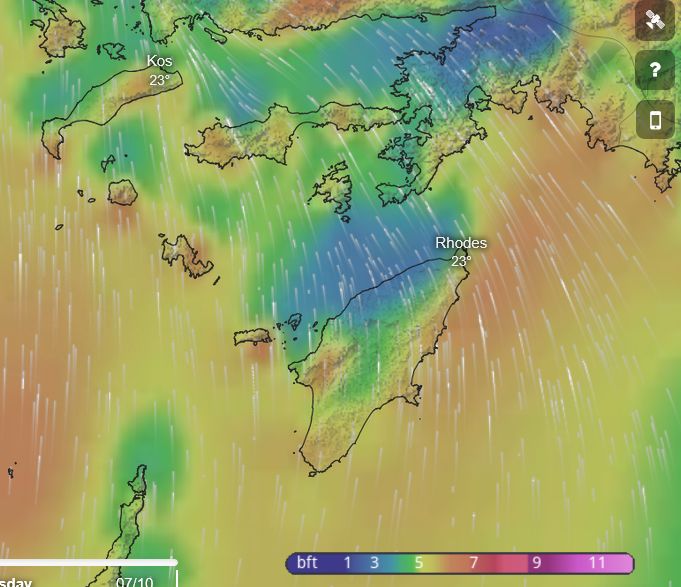

We’ve had a fabulously wet couple of days, the plants are thriving, the courtyard is a mess of fallen leaves and some flowers, and will be swept when dry, and Neil is traipsing down to Yialos this morning to get me some tablets and collect something from ACS while I battle on with the next story. The square and village were fairly busy yesterday afternoon and early evening, which is good to see, and there are still several day trip boats coming in every day, so the season’s not done yet.